Missions to Mars

Each dot represents a mission or series of missions;

Click on each to read about them, or click on the arrows to see more missions

Successful Mission

Successful Mission Failed Mission

Failed Mission

-

X

Marsnik 1 & 2

Launched: Oct. 1960

The Soviet Union’s space program had a long series of ambitious but failed Mars missions, beginning with these two attempted flybys. Both craft suffered third-stage rocket failures and failed to reach Earth orbit.

Photo: NASA

-

X

Sputnik 22, Mars 1, Sputnik 24

Launched: Oct.–Nov. 1962

In late 1962 the U.S.S.R. launched two more flyby missions, Sputnik 22 and Mars 1 (pictured), and one lander, Sputnik 24, all of which failed to complete their missions. Mars 1 was not a total failure, however; the probe traveled some 106 million kilometers from Earth before mission controllers lost contact, exploring a large swath of interplanetary space.

Photo: NASA

-

X

Mariner 3 & 4

Launched: Nov. 1964

NASA’s Mariner 3, which was intended to fly past Mars, failed to reach its destination when a protective shield did not detach after launch. Its sister craft, Mariner 4, was launched just weeks later but fared much better. Mariner 4 beamed back 21 images of the Red Planet, showing no system of Martian canals, as had been hypothesized by some astronomers, most notably Percival Lowell, nor any other signs of life.

Photo: NASA

In July 1965, at a distance of about 17,000 kilometers, Mariner 4 snapped this monochrome photo, humankind’s first close-up view of another planet.

Photo: NASA

-

X

Zond 2

Launched: Nov. 1964

This Soviet flyby mission went awry when its solar panels failed to fully open. Mission personnel lost contact with Zond 2 in May 1965.

Photo: NASA

-

X

Mariner 6 & 7

Launched: Feb.–March 1969

The identical spacecraft, launched one month apart, both completed successful flybys of Mars, returning hundreds of detailed images from up close and from afar.

Photo: NASA

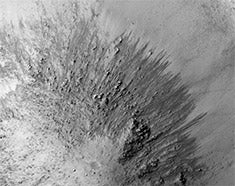

Mariner 4 had shown that Mars was cratered, but Mariner 6 and 7 painted a far more complete picture of the pockmarked terrain, imaging roughly 20 percent of the planet’s surface.

Photo courtesy of ASU/NASA

-

X

Mars 1969A & 1969B

Launched: March–April 1969

Both of these Soviet orbiters, which were to image the Martian surface, suffered swift mission failures when the Proton rockets used to launch them exploded shortly after liftoff.

Photo: NASA

-

X

Mariner 8 & 9

Launched: May 1971

These twin NASA spacecraft met very different fates. Mariner 8 encountered a launch malfunction and plunged into the Atlantic Ocean. But Mariner 9 succeeded in reaching Mars, becoming the first probe to orbit another world. A months-long dust storm, which obscured the entire planet, was raging when the probe arrived. After it eventually subsided, Mariner 9 mapped the bulk of the Martian surface.

Photo: NASA

Mariner 9 showed conclusively that Mars had seen volcanism in its past, including at Olympus Mons, the tallest volcano in the solar system. In this image from November 1971, Olympus Mons rises above the dust storm.

Photo: NASA/JPL

-

X

Cosmos 419, Mars 2 & 3

Launched: May 1971

The U.S.S.R launched three missions in May 1971, when Earth and Mars were unusually close together, minimizing the amount of fuel needed to hop from one planet to the other. The first craft, Cosmos 419, failed to leave Earth orbit, reportedly due to human error in programming the upper-stage engines to boost the probe onto a trajectory toward Mars. But with Mars 2, launched May 19, the U.S.S.R. finally found hard-won success. The spacecraft reached Mars orbit in November 1971, and Mars 3 (pictured) followed suit in December. Together the spacecraft measured Mars's surface temperature and returned dozens of images of the Red Planet. Each spacecraft carried a lander module; the Mars 2 lander crashed but the Mars 3 craft achieved a soft landing. It failed seconds later, however, for unknown reasons. Photo: NASA

-

X

Mars 4 & 5

Launched: July 1973

This pair of Soviet orbiters was a partial success. The braking system on Mars 4 failed, preventing the spacecraft from reaching Mars orbit, but the probe but did achieve a close flyby, taking photographs of the planet in the process. Mars 5 entered its intended orbit and in several days of operations returned about 60 images while also collecting data on the Martian atmosphere.

Photo: NASA

-

X

Mars 6 & 7

Launched: Aug. 1973

Mars 6 and 7 were intended to be flyby missions with landers. The Mars 6 craft successfully delivered its lander, which transmitted measurements of the Martian atmosphere as it descended to a presumed crash landing. Mars 7, however, suffered a glitch; its lander missed Mars by more than 1,000 kilometers.

Photo: NASA

-

X

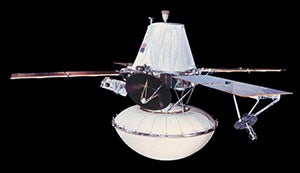

Viking 1 & 2

Launched: Aug.–Sept. 1975

Each of the Viking spacecraft comprised a Mars orbiter and a lander, each of the latter carrying dedicated experiments to detect biological processes on the surface. The two landers, which produced a wealth of images and data, looked in vain for evidence of life in the Martian soil.

Photo: NASA

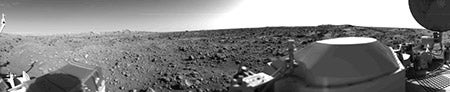

This image from the Viking 1 lander, taken in July 1976, is the first panoramic photograph ever produced of Mars's surface. Viking 2 ceased transmissions in 1980, Viking 1 remained operational until 1982.

Photo: NASA/JPL

-

X

Phobos 1 & 2

Launched: July 1988

The two Soviet craft were supposed to explore Phobos, the larger of Mars’s two miniature moons, with multiple landers. Phobos 1 succumbed to faulty software less than two months after launch and lost power en route to Mars. Phobos 2 fared somewhat better, successfully reaching Mars, but the craft malfunctioned just before approaching Phobos. As a result none of the landers reached the Martian moon.

Photo: NASA

-

X

Mars Observer

Launched: Sept. 1992

This orbiter was supposed to collect geoscience and climate data at Mars, but NASA lost contact with the spacecraft just days before it was to enter Mars orbit. Investigations pointed to a rupture in the probe’s propellant fuel line, which caused an explosion. If it did survive, without commands from Earth, the silent Mars Observer likely entered orbit on its own or flew past to be captured into orbit around the sun.

Photo: NASA

-

X

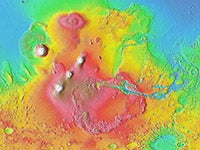

Mars Global Surveyor

Launched: Nov. 1996

After the loss of Mars Observer, NASA finally ended its long absence at Mars with the successful Mars Global Surveyor (MGS) mission. MGS carried out many of the geologic and atmospheric investigations intended for Mars Observer.

Photo: NASA/JPL-Caltech

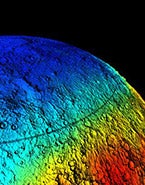

Among the MGS scientific instruments were cameras and a laser altimeter that produced detailed topographic maps of the planet. The craft lasted four times longer than planned. Its last communication was in November 2006.

Photo: NASA/MOLA Science Team

-

X

Mars 96

Launched: Nov. 1996

The first Mars mission of the post-Soviet Russian space program ran into the same troubles that plagued the early U.S.S.R. attempts to reach the Red Planet. Mars 96 was to orbit Mars and deliver two small landers and two impactors to the surface, but a failure in the third stage of its launcher sent the craft plummeting back to Earth.

Photo: DLR Institute of Planetary Exploration

-

X

Mars Pathfinder

Launched: Nov. 1996

Cushioned by airbags, the Pathfinder lander bounced onto the surface of Mars on July 4, 1997. It soon released the tiny Sojourner vehicle, the first rover to be deployed on Mars. The lander and rover performed measurements of the dusty Martian atmosphere and analyzed the chemistry of rocks and soil.

Photo: NASA

The Pathfinder lander camera photographed the 65-centimeter-long Sojourner examining a rock dubbed “Yogi” with its Alpha Proton X-Ray Spectrometer.

Photo: NASA

-

X

Nozomi

Launched: July 1998

This Japanese craft failed to reach Mars orbit after a mechanical malfunction put it on the wrong trajectory. A backup plan to use successive Earth flybys as gravity assists for a later Mars encounter was scuttled when solar flares damaged Nozomi’s onboard electrical systems.

Photo: NASA

-

X

Mars Climate Orbiter

Launched: Dec. 1998

The Mars Climate Orbiter was to study Mars's atmosphere, including its water and carbon dioxide cycles. But NASA lost contact with the probe and it plunged headlong into the Martian atmosphere. The mishap was attributed to a mix-up of measurement units between the operations teams—one team used the metric system and the other used English units.

Photo: NASA

-

X

Mars Polar Lander

Launched: Jan. 1999

This lander (launched separately) was to work in concert with Mars Climate Orbiter to study Mars’s climate and weather, but the lander also failed. As it entered the planet’s atmosphere, Mars Polar Lander was to release two probes (aka Deep Space 2) that would drop at high velocity, penetrate into the soil, and collect data on subsurface conditions. The lander itself was to have touched down near the carbon dioxide ice cap at Mars’s south pole. It also carried a microphone, which would have let humans hear for the first time extraterrestrial sounds. But spacecraft controllers lost contact with the lander just before it was supposed to enter the Martian atmosphere. It also never heard from the Deep Space 2 probes. Photo: NASA

-

X

Mars Odyssey

Launched: April 2001

This venerable orbiter has been in orbit at Mars since October 2001, making it the longest-serving Mars craft in history. The orbiter carries a Thermal Emission Imaging System and a Gamma-Ray Spectrometer to gather mineralogical information about the Martian surface as well as sniff out the possible presence of water.

Photo: NASA

This map of hydrogen, high concentrations of which indicate the presence of water, comes from Mars Odyssey’s Gamma-Ray Spectrometer, overlaid on exaggerated topography data from Mars Global Surveyor. The hydrogen-rich (blue) area in this image is near the Martian south pole.

Photo: NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center Scientific Visualization Studio

-

X

Mars Express & Beagle 2

Launched: June 2003

The European Space Agency’s Mars Express orbiter has been orbiting Mars since December 2003, measuring the composition of its tenuous atmosphere and returning detailed three-dimensional color imagery of the planet’s surface. Before entering orbit Mars Express released a U.K. lander, the Beagle 2, which presumably entered the Martian atmosphere but was never heard from again. The reason for the lander’s failure remains unknown.

Photo: ESA

This view from Mars Express shows Nili Fossae, an area where the orbiter has found hydrated minerals known as phyllosilicates. In 2009 researchers announced that Nili Fossae and a handful of other sites appeared to be producing localized plumes of methane, hinting at geochemical—or possibly biological—activity there. Photo: ESA/DLR/FU Berlin (G. Neukum)

-

X

Mars Exploration Rovers

Launched: June–July 2003

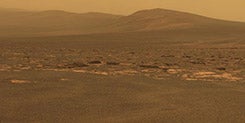

The Spirit and Opportunity rovers landed on Mars in January 2004 to carry out 90-day missions investigating the geology of the Red Planet. Both lasted much longer than that. Opportunity is still exploring Mars; Spirit became stuck in soft soil in 2009 and fell silent in 2010.

Photo: NASA

After a painstaking three-year journey, Opportunity reached Endeavour crater, an indentation some 22 kilometers wide, in August 2011. The giant crater bears signatures of clays and hydrated minerals indicative of the past presence of water; Opportunity will attempt to determine what kind of environment produced those minerals. Endeavour’s rim stretches into the distance in this photograph. Photo: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Cornell/ASU

-

X

Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter

Launched: Aug. 2005

This orbiter carries a number of scientific instruments, including HiRISE (High-Resolution Imaging Science Experiment), the largest telescopic imager ever deployed to Mars, and a radar instrument that has identified massive subsurface stores of water ice.

Photo: NASA

In August researchers announced that HiRISE images revealed transient, seasonal streaks on the surface of Mars. The streaks, which extend downhill over time, could indicate flowing briny water.

Photo: NASA/JPL/University of Arizona

-

X

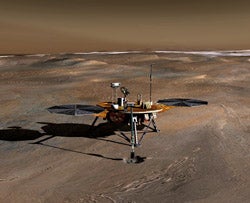

Phoenix Mars Lander

Launched: Aug. 2007

Phoenix touched down on Mars’s far northern plains in May 2008 to explore the surface there and to serve as a weather station. From its arctic landing site, Phoenix witnessed snow falling from Martian clouds and confirmed the presence of water in the soil.

Photo: NASA

Phoenix dug several trenches to sample the arctic soil. This trench, known as Snow White, showed extensive water frost accumulation as temperatures plunged toward the end of the Phoenix mission in November 2008.

Photo: NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona/Texas A&M University

-

X

Phobos–Grunt/Yinghuo 1

Scheduled Launch: Nov. 2011

Russia’s bold Phobos–Grunt mission will seek to collect soil samples from the Martian moon Phobos and return them to Earth for study. It will also carry a selection of microbes on the round-trip to test their ability to survive an interplanetary journey. China’s small Mars orbiter Yinghuo 1 will hitch a ride with Phobos–Grunt and, if all goes according to plan, become the first Chinese spacecraft to reach and orbit Mars.

Photo: Roscosmos

-

X

Mars Science Laboratory

Scheduled Launch: Nov. 2011

This automobile-size rover, also known as Curiosity, will dwarf its predecessors Spirit, Opportunity and Sojourner when it arrives on Mars in August 2012. Assuming, that is, that it touches down safely. The rover has an elaborate landing mechanism involving a parachute, rocket thrusters and a “sky crane” that will lower the rover to the surface. Curiosity carries a variety of cameras and scientific instruments; one of its prime goals is to determine whether Mars was ever hospitable to microbial life.

Photo: NASA