A Minefield in Earth’s Orbit

How the Space Debris Problem Is Spinning Out of Control

Like many other modern marvels, space exploration has yielded huge technological benefits for humankind, but it can’t help but have the same major side effect as many other advances: It has left a trail of garbage in its groundbreaking wake. The rockets, satellites and probes we have sent into orbit over the decades have created a fast-moving debris field that contains hundreds of thousands of pieces of space junk—even a one-centimeter piece of which can damage or destroy a spacecraft worth millions, or even billions, of dollars. The International Space Station and its crew have had to dodge dangerous debris several times in the past few years.

This threat has doubled in the past few years, thanks to antisatellite weapons testing and space collisions that are producing ever more debris. And scientists say that this space shrapnel is being produced faster than it will burn up in the atmosphere. This means that vehicles in orbit will face an ever-riskier path around the planet unless an international cleanup effort begins soon.

The headlines may focus on large pieces of space debris falling from the sky—even though such debris rarely hits land or causes damage—but the threat that urgently needs our attention, scientists say, is the massive and growing amount of space junk spinning above us. Here is our guide to the increasing dangers of this debris.

Tiny Pieces, Big Risks

As the chart below shows, even the smallest pieces of space junk can have catastrophic effects on satellites. And these small pieces make up the largest part of the debris field in low Earth orbit. Although NASA does track space debris there are some pieces too small to be counted—but they can still cause damage.

open/closeCategories of Debris

| Physical Size | Potential Risk to Satellites | Comments | Estimated Pieces of Debris in LEO |

|---|---|---|---|

| Larger than 10 centimeters (about four inches) |

Complete Destruction |

|

16,000 |

| 1-10 centimeters | Severe Damage or Complete Destruction |

|

400,000 |

| Smaller than 1 centimeter | Damage |

|

Unknown |

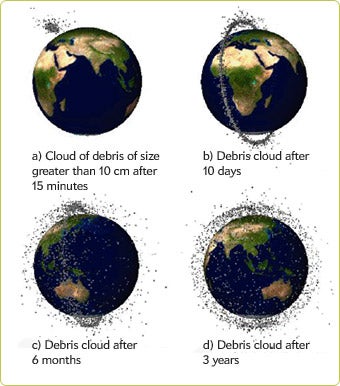

open/closeHow Objects Spread

These images are calculated by taking into account the NASA Breakup Model on the spread of fragments and by the asymmetries of the Earth.

(Source: Dr. Ting Wang, Stanford University)

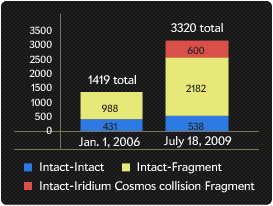

Number of conjunctions (close approaches of less than five kilometers) between LEO objects in a 24-hour period. (Collision risk is proportional to the number of conjunctions.) Fragments from a 2007 antisatellite test and from a 2009 collision between two satellites (Iridium and Cosmos) greatly increased the number of conjunctions.

(Calculation by Dr. Ting Wang, Stanford University)

The Cleanup Conundrum

It’s no surprise that the three nations with the most active space programs—Russia (including the former Soviet Union), the United States and China—have the most objects in orbit, including debris.

Whereas Russia leads the orbital field in terms of mass, China has the largest ratio of debris to spacecraft, owing to its antisatellite testing, which has created a large amount of debris.

These nations and others realize that hundreds of billions of dollars in satellites vital to communications, military strategy and environmental monitoring are on the line; the international community is beginning to make plans to clean up debris. Russia and the U.S. have already crafted some debris-removal proposals, and China’s recently unveiled five-year space plan has provisions for monitoring debris. Scientists who say the debris problem has reached a tipping point are urging space agencies to begin cleaning debris as quickly as possible, but legal and technological hurdles could stall such efforts.

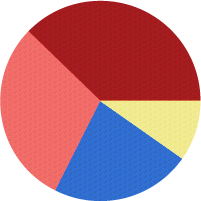

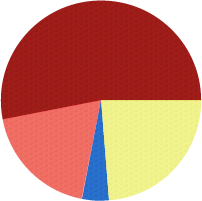

open/closeWhich Countries Own the Objects in Space?

An interesting way of looking at who owns objects in space is to consider the percentage of ownership by number of objects (left) and by mass of objects (right).

Russia*: 37.8%

Total Objects: 6,087USA: 30.1%

Total Objects: 4,850China: 22.4%

Total Objects: 3,615Others: 9.7%

Total Objects: 1,565

Russia*: 53%

Others: 24%

USA: 19%

China: 4%

*(Includes former Soviet Union)

Left: (As of 1/4/12, cataloged by the US Space Surveillance Network; Data from Orbital Debris Quarterly News, 1/12 issue)

Right: (As of 1/12, cataloged by the US Space Surveillance Network)

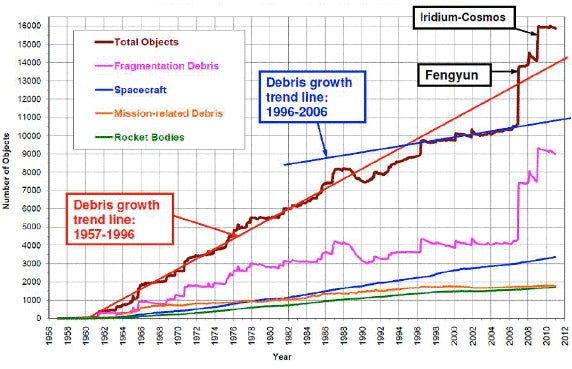

open/closeHistorical Growth of Space Debris Through 2011

The creation of space debris has followed a trend line—until very recently, when two events catapulted the amount of debris in space: A 2007 antisatellite test that blew up a one-ton weather satellite (Fengyun), and a 2009 accidental collision between a U.S. (Iridium) and Russian (Cosmos) satellite. China’s test brought international condemnation, and the Chinese government stated it would not conduct further tests. The Iridium-Cosmos accident prompted increased efforts at monitoring and limiting space junk.

Image based on objects in low Earth orbit (a region of space within 2,000 kilometers of Earth’s surface) that are currently being tracked by NASA. About 95 percent of these objects are space debris (not functional satellites). The orbital debris dots are not scaled to Earth. Click here for more information and similar images